MADHUBANI PAINTING: A DYING TRADITIONAL INDIAN ART FORM

As part of Laasya Art’s current focus on traditional Indian art forms, I wanted to take a moment to honor the prominent Madhubani (Mithila) artist Satya Narayan Lal Karn. He sadly passed away in 2015, but not before I had been lucky to meet him and to learn about Madhubani techniques and traditions from him.

I first came across Satya’s work in Bombay in 2011 at an exhibition on traditional Indian art. A lot of master craftsmen from different states all over India had traveled to show their art. I was immediately struck by how passionate and eloquent Satya was about his paintings, carefully explaining each symbol and scene to viewers. He obviously loved what he did.

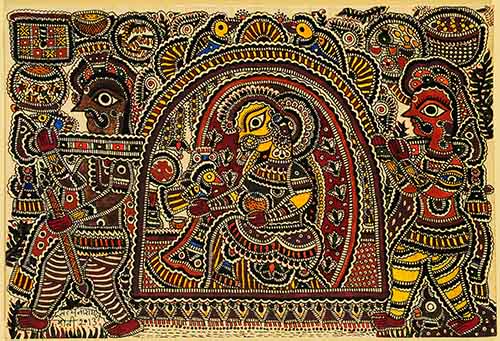

Satya could talk for hours about each of his paintings, and I always loved to hear the stories behind them. For instance, in a painting of a traditional Indian wedding, the daughter is shown traveling from her parent’s house to her new husband’s home in a ‘Doli’ or palanquin. Even the poorest Madhubani families in Bihar always send food — usually bananas and fish — with their daughter to her new home, to start her next phase in life in abundance and comfort. If they are wealthier and have the means to do so, they will also send a few maids with her to help her transition and to look after her.

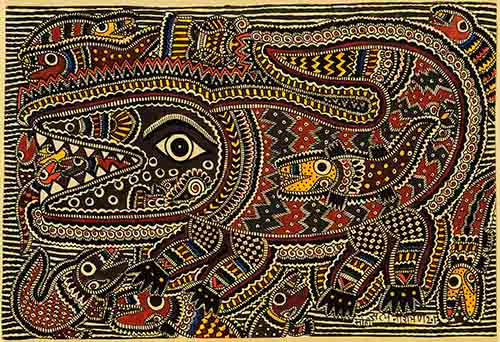

There are three main themes in Madhubani art, also known as Mithila art: religious festivities, social scenes like a wedding ceremony or even friends playing, and elements of nature such as elephants, crocodiles and fish. The Tree of Life, a sacred and multicultural symbol, is a common motif in Madhubani works. It is particularly important for its representation of sustenance, as human beings, birds and other animals all rely on the tree for shelter, food, water and oxygen.

Madbhuani works generally use only natural dyes, made from flowers, vegetables and leaves. Satya once said that he would never ‘take life’ to create art, so he would use only flowers or leaves that had already fallen from the bush or flowers left over at the temple. Sometimes he would get wilting flowers from a florist shop, when they were about to be thrown out after a long day. Before applying any ink or dye, the paper is treated with cow dung to keep the colors fast and strong. Cow dung is also mixed with charcoal for drawing the black outline. It is important to be in a very calm state of mind to make a Mithila painting— once the black outline is begun with a bamboo stick, there is no going back.

Satya also mentioned that the hallmark of a master Madhubani craftsman is that they will cover almost every single square inch of space on the paper with intricate designs. This requires a high level of finesse and skill, but it is also exactly what makes Madhubani art so special.

I frequently met up with Satya during his exhibitions in Bombay. Although he radiated such a strong belief and pride in his work, he confided that it was difficult to be a traditional artist and to raise a family. He wished there would be more support for traditional Indian art, not only from the government but from corporates art galleries and art collectors. He worked a full-time job in addition to pursuing his true calling. When I asked him about taking this second job, he said, “I can only do art if I have a free mind.”

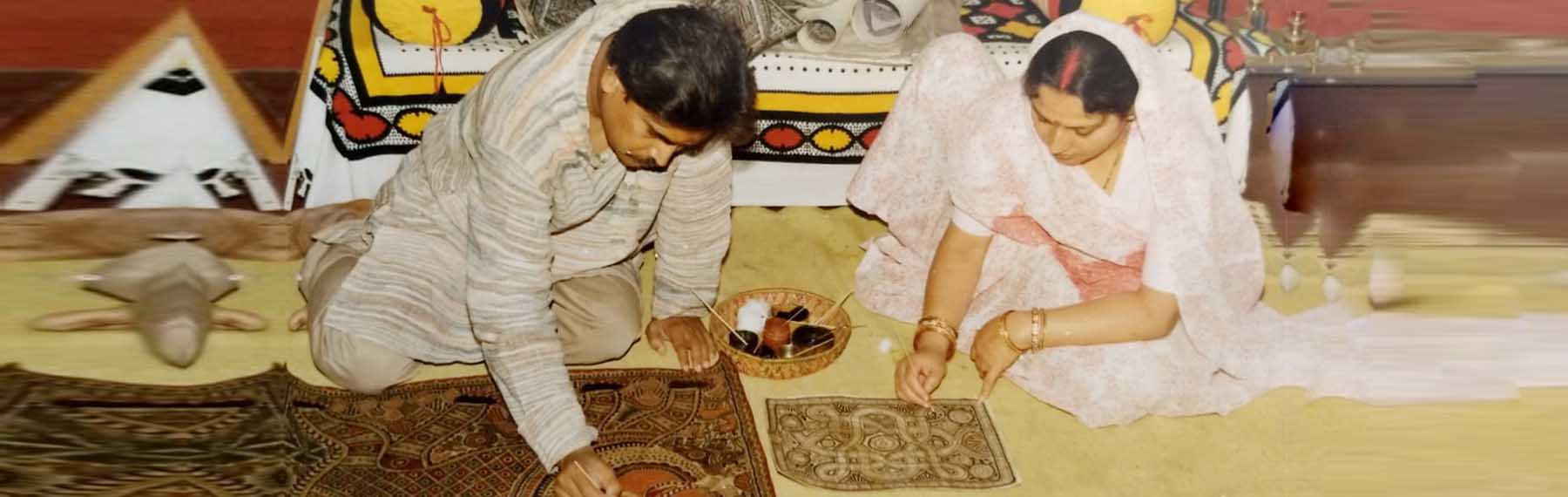

Satya was a generational artist, raised in a family of Madhubani artists. His foster mother Jagdamba Devi played an important role in his passion and training, as she was not only a Madhubani painter herself but the first artist to receive a National Award in Mithila paintings and a Padma Shri awardee. Satya’s wife Moti Karn is also a well-regarded Madhubani artist, and together they would work on paintings each night after dinner. If you look at the paintings closely, you can see the mixing and intertwining of their unique styles. In 2003, Satya and Moti jointly won the National Award.

The last time I saw Satya on one of my visits to India, I told him I was opening an Indian art gallery in California to promote both traditional and contemporary Indian art. He mentioned that he had bought land in his village, hoping to build a school to teach the dying art form to local children. Sadly, he passed away soon after that of a sudden heart attack, so the school has still not been built.

Even though he was unable to realize his dream of opening the school, Satya Narayan Lal Karn has left behind a rich legacy to admire and preserve. When I think of him, I think of someone who had immense pride in his culture, his skill and his work. In his memory, I hope to find more robust support for the traditional arts in India and to help Madbubani painting thrive.

This month at Laasya Art, we are highlighting traditional Indian folk art including Madhubani (Mithila) paintings to encourage a new wave of appreciation and support for traditional craft artists. To browse our curated collection of Madhubani paintings online, visit https://laasyaart.com/mithila-art. Please reach out to us at info@laasyaart.com or 650-770-9088 to view these traditional works in person at our gallery in Palo Alto (San Francisco Bay Area).

— Sonia Nayyar Patwardhan

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.